Cultivate Family Readiness for Change

As families of wealth and their Family Offices consider future success strategies, how ready are they to adapt? In this excerpt from our 2020 FOX Foresight publication, FOX Chief Operating Officer, Glen W. Johnson, talks with Dr. Jim Grubman about the approach he uses to help families and their Family Offices successfully navigate change.

GLEN JOHNSON: How did the “Stages of Change” model in a family system come about? How did you adapt it to help families manage change?

JIM GRUBMAN: The original model for the Stages of Change comes from research done in the 1970s and ‘80s around habit control. Researchers looked at the behavioral patterns occurring when people changed habits, like stopping smoking, starting to exercise, or dieting. What they discovered was the process of making change was remarkably predictable and independent of any personality theory.

GJ: How did this work move into the family systems field?

JG: Most of the research and literature is focused on individuals. I initially adapted it to understanding financial behaviors such as reducing overspending, which can be a very difficult habit to break. From there, I started to take a more systemic approach, and I began to see how the behavior patterns for individuals could be helpful when working with families.

GJ: What parallels have you seen between personal and family behavioral change?

JG: One of the most important parallels is that individuals may agree to change, be compliant with others who want to change, or say they understand the need for change. However, this doesn’t mean they are truly ready to change. Similarly, some families may understand intellectually what is needed but aren’t really ready to do the work to implement it. It is important to recognize the reality of that disconnect both for an individual as well as for the family.

“Researchers looked at people’s behavioral patterns as they changed habits, like stopping smoking, starting to exercise, or dieting. What they discovered was the process of making change was predictable and independent of any personality theory.”

GJ: Beyond adjusting spending habits, what other family changes follow the same model?

JG: Families—particularly ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) families like FOX members—encounter similar patterns with many important and difficult changes. It could be around improving governance and decision-making, or dealing with generational or family business transition planning. Not everybody may be of one mind when it comes to the need for change, or when or how it should happen. As a result, families can get “stuck.”

GJ: What other complexity exists within UHNW families?

JG: UHNW families have a larger group of interested and involved family system stakeholders who must be brought into the process. They range from attorneys to Family Office executives, accountants, and other advisors. Each has some opinion about whether change is needed or how it should occur.

Family Office executives often play a critical yet difficult role. Sometimes the family wants to make a change and they look to the Family Office executive to facilitate it. At other times, the Family Office leader sees the necessity for change, but the family may not be ready. That is one of the most frustrating situations for a Family Office.

GJ: You’ve helped family members and Family Office executives analyze the change process, using a tool called the Readiness Ruler (Fig. 1). How does that work?

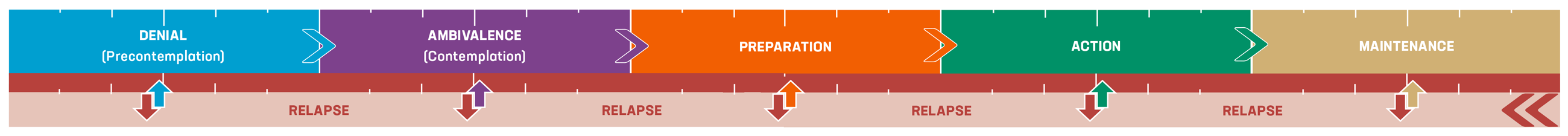

JG: The Readiness Ruler has five progressive stages related to any specific change—plus a sixth stage that can occur at any time.

Figure 1: Jim Grubman’s Readiness Ruler (Click image to view larger.)

The Readiness Ruler in stages of change. Adapted from material by James Grubman, PhD. Used with permission.

The Readiness Ruler in stages of change. Adapted from material by James Grubman, PhD. Used with permission.

- The first stage is precontemplation, more commonly known as denial—somebody does not see any need for change. They may not be ready for any change or don’t agree on its necessity and may actively resist.

- As people begin to contemplate the change, they enter the ambivalence stage—they’re on the fence. They may see advantages to making the change but may not quite be ready for it. They may be more focused on the disadvantages, think it’s too difficult, or just may not have the energy or interest for it.

- After spending days, months, or even years in ambivalence, people may start to enter the preparation phase. They start to think about what would be involved in doing the change; they begin making a plan. That doesn’t mean they go through with it, however. For example, you may have a personal goal of going to the gym more often. Entering the preparation phase means you may start thinking about which local gym might be best. Or you may look at workout clothes when you’re shopping. You may investigate what kind of exercise might work best. You are beginning to prepare for the change.

- If the planning is productive, people can move into the action stage of implementing the change itself. They actually do the hard work to make it happen. They may find it’s easier or harder than they thought, and they deal with setbacks or successes.

- If that phase is successful and the change is cemented, they move into the maintenance stage where the change becomes the “new normal” and is now their status quo. The change is sustained.

GJ: Does every family need to move through these five stages for change to occur?

JG: The changes are not rigidly determined, though this general pattern often applies. Some of the changes may take place so quickly it seems we’ve skipped them. However, truly skipping a stage can have drawbacks. I’ve worked with families, for example, who were ambivalent about creating a family council. Once resolved, some jumped very quickly to action without doing adequate preparation and planning. As a result, it can fail. Then people get discouraged and the family retreats, saying, “well that was a failure, we’re not going to try that again.”

GJ: This is the sixth phase called relapse, right? We often link relapse with addiction, but it also affects family issues.

Why is relapse important in this journey?

JG: Relapse is normal and natural to all change. It can provide tremendous learning opportunities by showing us our hidden risks and vulnerabilities. We may have overlooked something or did not realize certain risks existed.

Relapse can occur at any stage. The most important thing is whether you accept relapses as learning opportunities, join together to improve the plan, and move forward again in a more informed way.

GJ: Where do you start when using the Readiness Ruler with a family?

JG: When approached by either a family member or the Family Office saying the family is “stuck,” I initially do an assessment to determine where various people or family factions are on the Readiness Ruler. Are there enough people who really understand the need for change, agree on it, and are ready to do the necessary work? Or, as I often find, are there really only a couple people gung-ho to make some change, but the rest of the family either doesn’t see the necessity or is not with them? That’s often why the family appears “stuck” in the view of the ones who want to get going with things.

GJ: What critical elements are needed to assess where people are on the Readiness Ruler?

JG: The most critical element in an assessment is listening. If you ask open-ended questions in a nonjudgmental manner, then really listen, you’ll hear a variety of responses that place people along the Readiness Ruler.

People may say, “Well yes, I know they’ve been talking about that, but it seems like a big project to me and I’m not really convinced we need to do that.”

Or you may hear, “Well, I can see some benefits to doing it but I’m just worried how long it will take. I’d like to see more of a plan. I think if there were a decent plan, I’d be willing to go along.”

Another person might say, “Oh yes, I’m on board. I think what we need is to understand what’s going to be involved with a timeline, budget, and the specific steps.”

Each of these responses reflects a point along the Readiness Ruler.

Another critical element is to observe. People may nod in agreement about creating family governance or changing advisors, but I watch to see what their behavior reflects. Do they participate in the work that’s needed? Do they attend meetings? Do they join a work group? Or, do they express support but there is no follow-through?

I will meet with the entire family at a family assembly, or with the family leaders or Family Office executive who requested my assessment, and I’ll explain what I’ve found.

“I watch to see what their behavior reflects. Do they participate in the work that’s needed? Do they attend meetings? Do they join a work group? Or do they express agreement but then sit back and do nothing?”

GJ: Can you share some examples of what you have uncovered during an assessment?

JG: Often, change starts with a single person we call a “family champion.” In one situation, there was a third-generation individual who had been able to garner support from a few others in the family for designing a family governance change. She reached out to me for help. The problem was, out of twenty-three people in the family, only four really understood the necessity for change or wanted to work on it. Everybody else either was in the dark or did not see the wisdom of the project. I had to break it to the four family members they did not have adequate support for the project. Rather, they needed to back up and spend more time laying the groundwork to get people onboard. Otherwise, they would be encountering tremendous difficulty when they tried to initiate the project and were likely to fail.

In another family, the opposite occurred. Most people saw the need to improve family governance but were frustrated because the patriarch was resisting any change and had a few other senior family members aligned with him.

While there was a critical mass of people ready to move forward, it did not include the family’s main influencers and holders-of-power who were still in ambivalence. In that case, I worked with the broader family to hear the concerns and the risks the elders were seeing. I also provided some information to the family leaders. Ultimately, the elders began to recognize the benefits of moving forward. We got the system “unstuck” and the family was able to move ahead.

GJ: Earlier, you described a family champion. What is the role of a family champion, and does every family need one as they go through change?

JG: Not everybody needs a family champion if they have strong leadership and can move forward on important projects for the family. However, family champions can play an essential role if those elements aren’t present. Family champions are often from the rising generation, advocating that the family move forward in a particular direction. What’s important is whether they can generate a critical mass of support—not just leading a reluctant family forward, but gathering people who see a project’s wisdom and want to participate.

GJ: In everyday life, we regularly use the term “denial.” How is that different in this process?

JG: There is a heavy risk of being judgmental when labeling somebody as being in denial. Someone may just have a very different perspective—that their position is perfectly fine, correct, and that others are pushing for unnecessary change. So they’re not in denial; they’re actually resisting a project they think shouldn’t occur, which very well may be correct.

When I do an assessment, I go in without preconception as to who is in denial, who is prepared for change, and which faction is “correct.” Rather, I try to defuse name-calling or accusations and try to get the family members to look at the pros and cons of any proposed change. The goal is to have them negotiate some agreement or solution together.

GJ: How do you most effectively influence someone who doesn’t see the wisdom of a legitimately good project or change?

JG: The most important thing for the family, or the Family Office executive, is to preserve relationships with someone who is very firm in their position. Rather than name-calling, you need to ask open-ended questions and use active listening to understand the other person’s position as best as possible. Don’t try to contest it, just try to understand it. When they see you genuinely are trying to understand their position and not constantly debating them, they’ll feel understood and appreciated.

In the future, that person may be more ready to consider the change. If you’ve damaged your relationship with someone originally in denial, you may lose them as a supporter when they are ready to move ahead. If instead you were respectful earlier, you will have preserved your relationship so you can work with them, and they’re willing to work with you and others.

“Someone accused of being ‘in denial’ may just have a very different perspective—that their position is perfectly fine, correct, and that others are pushing for unnecessary change. So they’re not in denial, they’re actually resisting a project they think shouldn’t occur, which very well may be correct.”

GJ: How do you work with people who are ambivalent, or as you say, “on the fence?”

JG: Research has shown that if you try to persuade an ambivalent person by starting with the benefits of change, it often generates a counter-reaction. They will come back with reasons against, or to maintain the status quo. It is more effective to start by acknowledging the many reasons not to change. Interestingly, the person in ambivalence may then comment on the benefits of moving ahead and why the status quo actually may not be advisable in the long run.

It can also be helpful to “work with the willing” and do a small pilot project demonstrating the change, which later could be expanded for the broader family.

GJ: What would be an example of a smaller project?

JG: When a family is beginning to develop family governance and may not yet have a family council, a favorite technique is to help them form a workgroup. I choose people with energy and enthusiasm but who may not have much education or knowledge about family governance. As I consult with the workgroup, we’ll work together on planning a few initial family assemblies. Gradually, over time, that workgroup may be the seed for the first family council. When framed as a workgroup, though, it’s less threatening to the family while serving as a bit of a family governance incubator.

GJ: Help us understand the need for critical mass in the family to move forward, and in which stages.

JG: It’s advantageous to have a critical mass of people, in terms of numbers or influence, to be at least in the ambivalence stage—even better, in the preparation stage. Frankly, preparation is probably the best stage to be in to move toward action. A critical mass can mean either a true majority of the family or enough of those who have genuine power in the system. You may need quite a few people, or you may only need three. If they’re family leaders, that’s all you may need.

GJ: How do you adapt this approach when working with a large multigenerational family?

JG: Large systems can be very complicated because the common distinctions we make—by generation, or age, or family branch— may hide the real family distinctions concerning a proposed change. Perspectives on transition planning, family governance, or the family business may cut across generations or branches of families.

What you’re really looking for are the factions and alliances. An alliance on a particular issue may include one person from the second generation, four from the third, and seven from the fourth, as opposed to most of one generation or whole branches of a family. Look beyond surface labels to the genuine feelings about the issue. Then you can determine whether you have sufficient support for working on change or whether it’s going to be very difficult and slow.

GJ: Any final thoughts or advice for families and Family Office executives as they consider how to best use this model to foster family change?

JG: Assess accurately, try to be nonjudgmental about all the various factions, and work to build critical mass so there’s adequate support for any change. This may take more time than you think. Try not to work from your own view on what needs to be done. Recognize this is about readiness for change within a family, not just the advisability of change. People won’t work together for something if they are not ready to do so.

~~~

Dr. Jim Grubman has provided services to individuals, couples, and families of wealth for more than thirty years. His work at many levels of affluence has earned him a reputation as a valued family advisor. Jim draws on his experience as a psychologist, neuropsychologist, and family business consultant with specialty interests in trusts and estate law, family governance, and wealth psychology. Over the years he has been a frequent guest and speaker at FOX events, sharing his wisdom and insights around the complex issues of wealth within family systems.

Dr. Jim Grubman has provided services to individuals, couples, and families of wealth for more than thirty years. His work at many levels of affluence has earned him a reputation as a valued family advisor. Jim draws on his experience as a psychologist, neuropsychologist, and family business consultant with specialty interests in trusts and estate law, family governance, and wealth psychology. Over the years he has been a frequent guest and speaker at FOX events, sharing his wisdom and insights around the complex issues of wealth within family systems.